Table of Contents

Topic 2: Anatomy of an ADR clause

This is the second article in a series of five articles on alternative dispute resolution (ADR).

This article will look at the different parts an ADR clause may contain, and analyse two ADR clauses from template agreements in the Zegal database: a Business Collaboration Agreement and Partnership Agreement.

The first article in the series titled “Do’s and Don’ts for ADR clauses”, can be viewed here .

The next article will explain the mediation process, its pros and cons, and the new United Nations convention on mediation.

Elements of ADR clauses

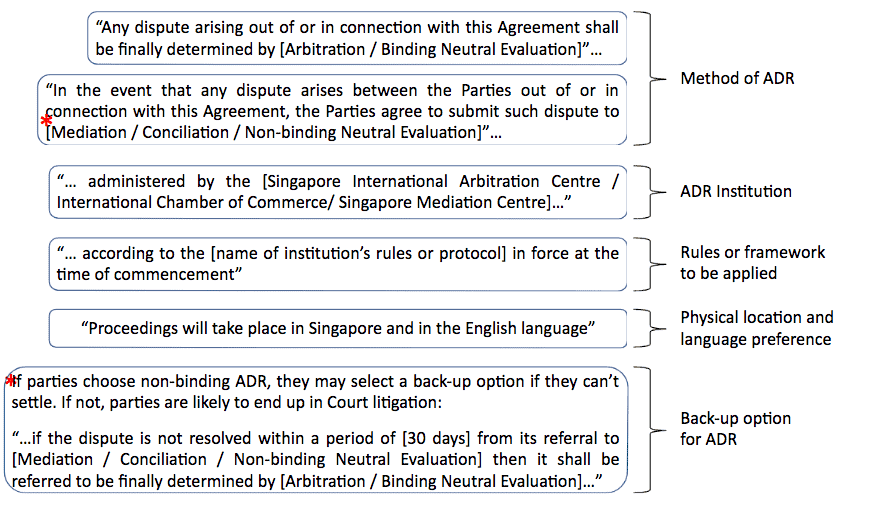

A typical ADR clause may contain the following elements:

A properly-drafted arbitration clause tends to be more complex than other types of ADR clauses and needs more elements than those above, such as the seat and law of the arbitration agreement.

How does this work in practice?

Even the best ADR clauses cannot predict the future. It may well turn out that parties are unhappy with the ADR method they have agreed to use. Or worse, were not aware of what they signed up for. Crucial elements of the clause may also be missing when the time comes to settle a dispute.

However, a skilled lawyer will do the next best thing – by keeping in mind the underlying nature of the contract and the commercial realities facing the parties, they can develop a dispute resolution clause that will suit the situation and help the parties achieve their goals as far as possible.

Her are two examples of how this works:

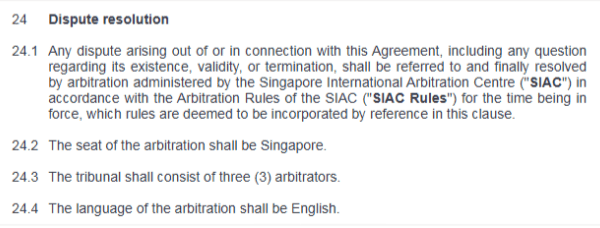

Business Collaboration Agreement

There are different ways that people or businesses can work together and combine their resources, whether through an informal memorandum of understanding or a highly-structured joint venture. This template agreement falls somewhere in between.

The parties going into this agreement may want to keep working together for a long time, if it makes good financial sense to do so. They may have important business synergies that they need to preserve, or may depend on the agreement to stay ahead of a competitor. They may also have trade secrets or other issues which they want to shield from public view.

In this case, mediation may be a good first step to take when these parties run into problems, as it is generally confidential, may help to preserve the relationship, and allow the parties to find a compromise or even a win-win solution.

However, not all problems can be resolved this way. If the parties fail to reach an agreement, they may need a third party to make a binding decision for them so they can close the matter and move on. Therefore, confidential arbitration may be a suitable back–up option if mediation fails, but it will not necessarily preserve the relationship and allow the parties to keep working together.

Alternatively, the parties’ agreement may be complex and any dispute might involve large sums of money. The collaboration may also be short-term and the parties may prefer to go straight to arbitration to resolve any dispute, rather than discussing it before a mediator. This is reflected in the sample clause below:

This sample provides for any dispute to be sent straight to arbitration before three arbitrators, which would be suitable for a complex or high–value dispute. In general, each party has the power to pick one arbitrator each, and their picks will nominate the third member of the panel. Parties can also decide in advance that one of the arbitrators must have experience in their industry.

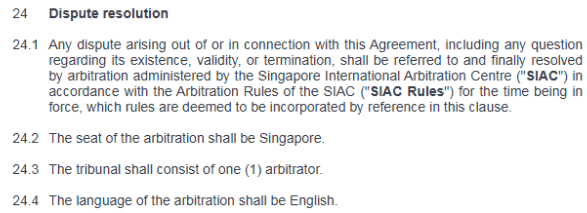

Partnership Agreement

A partnership agreement allows individuals who intend to carry on business using the partnership structure (often used by lawyers or accountants), to set out their responsibilities, rights, profit sharing arrangement, etc.

In these circumstances, if the partnership breaks down, it is unlikely the partners will continue to work together. Therefore, slightly different considerations may come in compared to the earlier example. The parties may be professionals who are concerned with keeping their reputations intact and avoiding a public spat. There may be industry-specific matters which they need a neutral expert to help them wade through. Some may want to avoid expensive legal costs and end the partnership in a way that lets everyone walk away with more money than a long drawn-out fight would allow.

In this case, mediation or non-binding neutral evaluation by an expert from the same industry as the parties (e.g. lawyer or accountant-mediator), may be a good first step. Parties could choose arbitration as a back-up or as the only method of dispute resolution.

Here, the sample clause provides for parties to go straight to arbitration before a single arbitrator:

Using a single arbitrator is useful in keeping costs lower for smaller and less complex disputes. Further, the flexibility of arbitration allows parties to choose a decision-maker who is an expert in their industry, such as an accountant-arbitrator to decide a dispute for an accounting partnership.

Conclusion

As you can see from the examples above, an ADR clause can have many or few moving parts, and can provide tailored solutions to suit the specific agreement between parties. Alternatively, parties can save time and choose an ADR option without going into any detailed analysis.

With the second approach, it is still important to be sure that the ADR option is actually suitable for the type of contract. For example, it is not unusual for a three-arbitrator clause to appear in a low value agreement (e.g. a simple tenancy agreement), because the parties didn’t realise that this will significantly increase their costs in a dispute.

Typically, ADR or dispute resolution clauses are known as “midnight clauses” because they are often jammed in by parties as an afterthought – no one wants to think about their exciting new business deal going wrong. However, it is in parties’ interests to take the opportunity before signing to discuss the best way to work through their differences. That way, when problems happen later on, there may still be a chance for everyone to walk away with something.

General disclaimer: Please note that this article is intended as a general guide on the subject matter and should not be treated as legal advice. It is to your benefit to seek specific professional advice tailored to your situation or business needs. All views expressed above are the author’s personal opinions.

Farrah Isaac is a lawyer at Eversheds Harry Elias LLP, the Singapore office of global law firm Eversheds Sutherland. She specialises in managing and resolving commercial disputes through arbitration, litigation, and negotiation, and assists clients ranging from large multi-nationals to small and medium enterprises, including start-ups.

She is also experienced in advising clients to manage the risks of or avoid disputes through proactive planning, and in providing straightforward and cost-effective advice and solutions.

For further information or questions about her articles, connect on LinkedIn or get in touch by email at farrahisaac@eversheds-

This article does not constitute legal advice.

The opinions expressed in the column above represent the author’s own.

READ MORE: Your Complete ADR in Singapore Toolkit: Dos and Don’ts for ADR Clauses